Source: www.ledgerinsights.com

Last week, Bloomberg reported that prosecutors are investigating possible fraud related to FTX’s transfers to the Bahamas, presumably those made shortly before bankruptcy. However, there are fundamental unanswered questions about the early days of FTX, when customers transferred money to FTX through Alameda.

Former FTX CEO Sam Bankman Fried (SBF) stated that FTX lacked a bank account in the early days, so customers wired money to Alameda. And these transfers represent a significant amount of the funds owed by Alameda to FTX at the time of bankruptcy.

This raises two related questions:

1. When Alameda received money from clients, why didn’t he buy stablecoins and transfer the coins to FTX?

2. If FTX did not receive the cash from Alameda, how did FTX buy cryptocurrency so clients would keep the assets fully backed?

Before we explore the questions, let’s look at how fraud is defined. Put simply, fraud is when someone suffers a loss related to a misrepresentation. For example, declaring that your assets are backed one by one when they are not. Civil fraud is often the result of carelessness or negligence. There is a need to show that someone did something on purpose to prove criminal fraud, and this is the one that could potentially land you in jail.

Why didn’t Alameda transfer stablecoins to FTX?

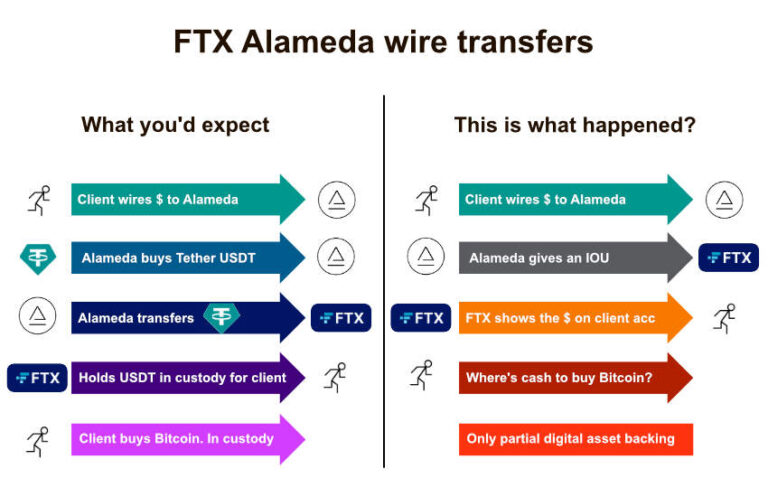

According to Bankman Fried, when customers transferred money to Alameda intended for FTX, Alameda essentially viewed it as a promissory note to FTX (the promissory note is our shorthand). On FTX’s books, clients were shown to have money, and Alameda’s account at FTX was overdrawn by the same amount.

That looks bad.

If FTX intended to do right by its customers, this treatment is very strange. It is about whether or not FTX had good intentions towards its clients.

Ignoring how the transaction was dealt with, going to first principles, this is what should have happened:

- Customers send money to Alameda

- Alameda buys the equivalent in stablecoins

- Alameda transfers stablecoins to FTX

- FTX now has stablecoins in custody belonging to the client

- The client asks FTX to use stablecoins to buy, for example, Bitcoin, which it has in custody.

if this had happenedthere would be no intercompany balance between Alameda and FTX.

Yes this was not the route taken. Why???

It is also worth noting that Alameda Research is one of the two largest brokers for distributing newly minted Tether stablecoins. Protos found that Alameda has distributed more than a third of all newly minted Tether. And Alameda’s activity is mainly since FTX started.

The vast majority of the newly minted stablecoin, over $30 billion, has gone directly to FTX.

So it’s not that the option of providing stablecoins to FTX in exchange for the transferred money seemed strange to Alameda. It would have been by far the most obvious scenario.

And the Protos figures imply that this could have been what happened.

Besides, during the early days when this methodology for wire transfers was developed, SBF was the CEO of both companies and the number of employees was low. It is inconceivable that SBF was not involved in deciding how to treat wire transfers.

Stablecoin Conclusion:

a. Or Alameda transferred stablecoins, in which case, SBF wrongly indicated the Alameda balance related to wire transfers when it did not. In which case, how did Alameda’s balance sheet get so big?

EITHER

b. Alameda kept the money and gave FTX an IOU, which seems like knowingly bad attitude on the part of FTX towards its clients.

EITHER

C. Alameda minted stablecoins but held them and still gave FTX an IOU, which also looks bad.

How did FTX buy coins for clients without the money?

Suppose that when clients wired Alameda, FTX did not receive Alameda’s cash or stablecoins (as SBF has stated). So how did FTX buy currencies for clients?

Without FTX having massive capital reserves, the most likely answer is that FTX client assets were not fully backed. And that’s not just recently.

If all clients simply parked their cash and crypto at FTX and only traded spot, then it could provide an opportunity to prosecute fraud early on. And there could be the possibility of arguing that ‘cash only’ customers were defrauded.

However, SBF continues to insist that some clients agree to lend funds and many trading derivatives on margin. You’re trying to make the case that it was okay for these clients if the backing was a combination of digital assets and the Alameda promissory note.

The problem is that the digital assets of ‘spot only’ clients should have been segregated from others to ensure they were always backed up one by one. Was the desegregation negligent or intentional?

That relates to the first question. Did the creation of Alameda’s intercompany balances show a disregard for customers in the first place? If a prosecutor can prove intent, then the fraud was a crime.

Read More at www.ledgerinsights.com